Below are some images taken with the Sony a7 III(m) by Portland Photographer Norm Eder. The images were sent to me to use here, and were processed by the photographer.

He has also been kind enough to give some thoughts about how the AF of the converted a7 III(m) performs compared to the non-converted camera, and the camera in general.

See below for his evaluation.

I asked Daniel to convert a Sony A7 III camera for me after much discussion about what features might be lost after completion.

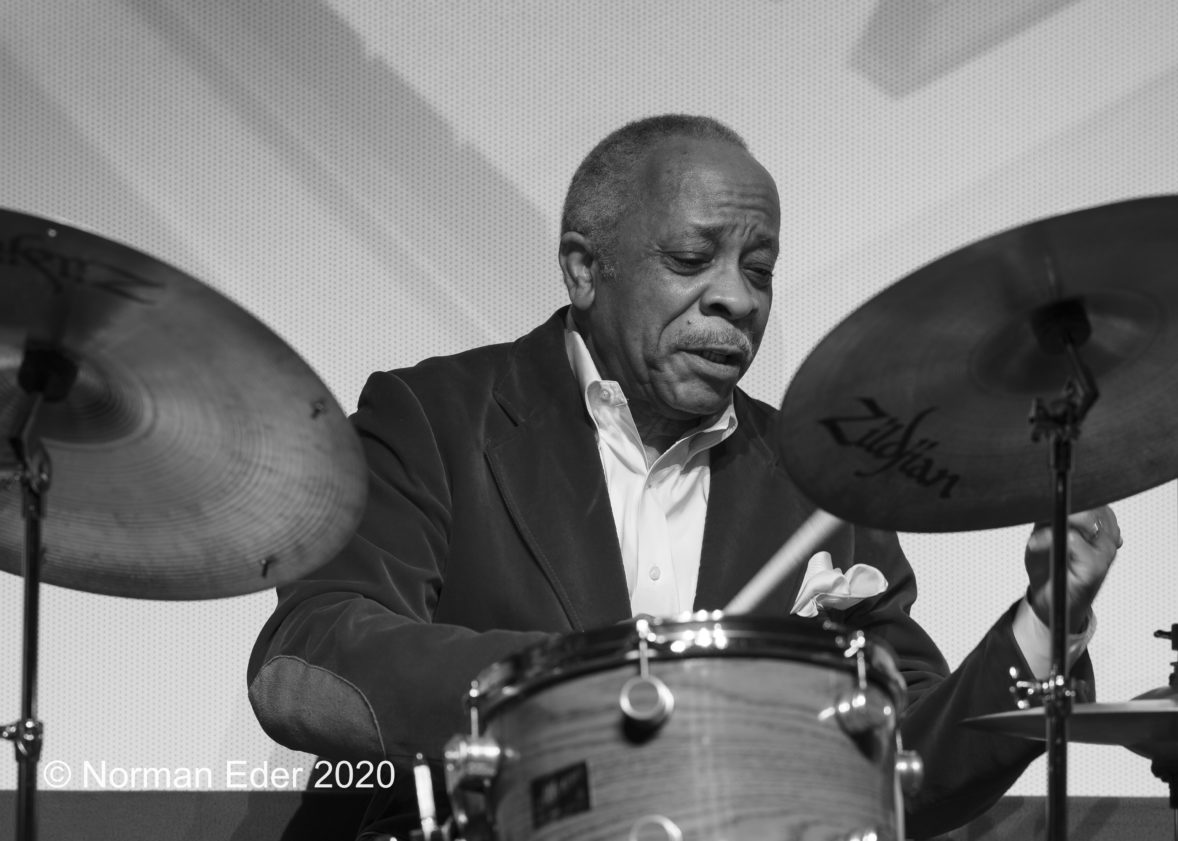

My intended use for a dedicated black and white camera is for stage performances, particularly music. Performance photography, whether for theater or music is tricky. Stages are not evenly lit side to side and front to back. Music performance lighting is often decidedly more blue and red, and often with strobes. Color correction for these extreme conditions in post processing only goes so far, even when shooting raw. This is why a dedicated monochrome camera seemed like a step up from post processing a digital black and white conversion from color, which can sacrifice sharpness and produce unnatural tonal transitions.

I was not concerned about the quality of the images I could achieve with a converted Sony a7 III(m). I particularly liked the idea of gaining a stop in low light. I was, however, very interested to see how the camera’s excellent focusing and tracking features would be altered after conversion when the camera’s phase detect system was no longer available. This issue may not matter much to landscape, night sky and portrait shooters, but it was important to me. Shooting performances are similar to athletic events. A camera that cannot snap into focus is a frustrating tool when working around in a packed house.

Daniel and I engaged in a long email discussion about how Sony camera’s make use of phase detect and more traditional contrast focus.

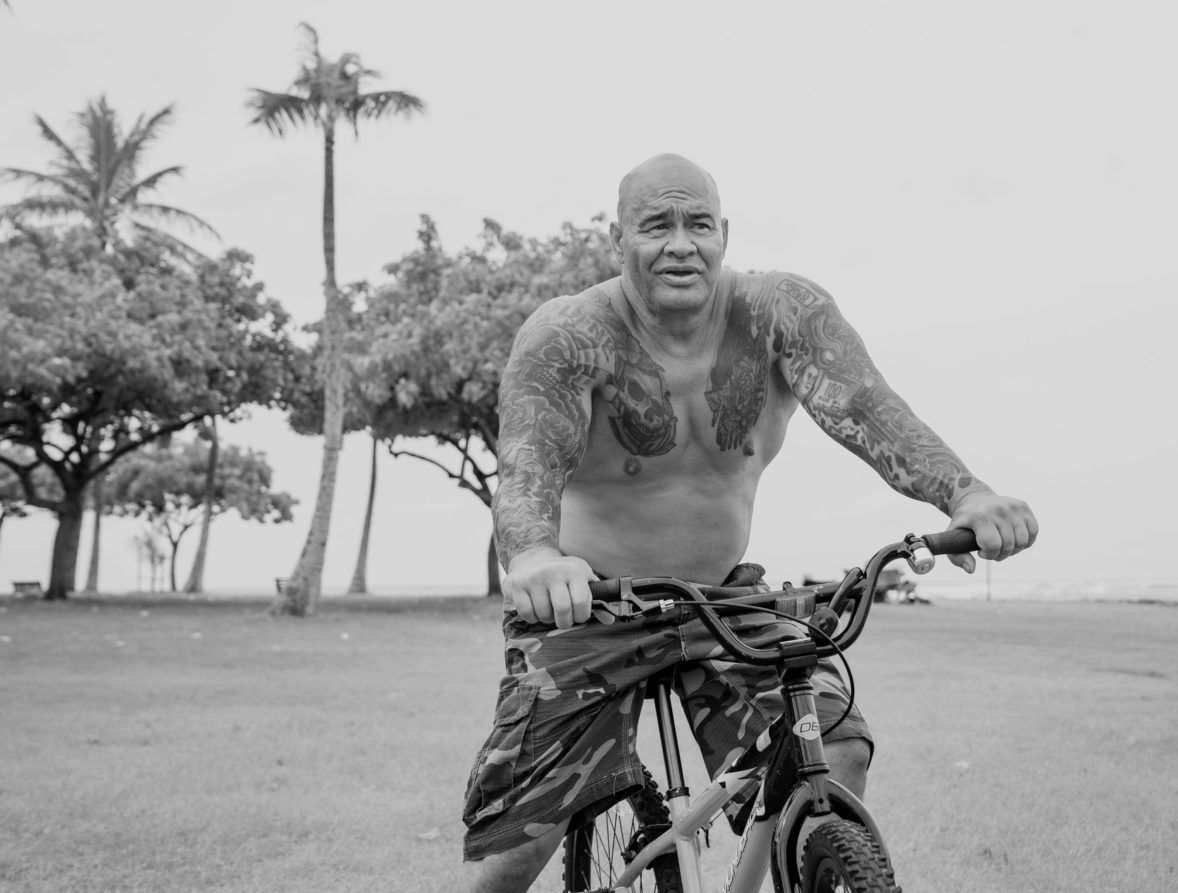

I’ve used my converted camera for about a month for performances, street photography, and landscapes. I chose a full conversion, meaning the camera is a full spectrum IR camera when used in sunlight.

- The monochrome images coming from the converted Sony a7III(m) 24mp are spectacular. The tonal contrasts are smooth and subtle and very detailed when using Sony’s G Master lenses. Minor adjustments in post processing is all that is needed to satisfy personal preferences for B&W contrast.

- The camera clearly relies only on contrast to achieve focus. I compared the converted camera to an identical unconverted a7 III and it and does not seem slower in achieving its target. The more contrast, the faster the focus, just like older auto-focus cameras.

- The loss of phase detect capability affects the functionality of the camera’s ability to track targets. Focus tracking no longer seems functional, or at least it does not work well enough to make it useful.

- The eye focus system still operates, but with the loss of tracking capability, this too has been degraded by the conversion. The camera locks on eyes but then quickly defaults to a wider area focus when movement is detected. This means photographers must take more care when shooting wide open – just like the old days before the advent of accurate tracking technology.

- Lightroom supports global black and white conversion (V). MonochromeDNG, works well but I found Lightroom produced a very similar result with a direct import from a data card. On1 does equally as well, either as a stand-alone or as a Light Room plug-in.

- If you are shooting with more than one body (monochrome and color), you should import your monochrome images and run them through the Lightroom global conversion before you import color images—if your intent is to keep both files in a single folder or collection.

The bottom line. Conversion to monochrome adds a great tool to your bag. Still perhaps the best part is the camera allows thinking and seeing in monochrome; adding to, or for some of us, restoring a diversity to the photographers experience.

Norm Eder, Jan. 27, 2020

All rights remain those of the photographer, Norm Eder, 2020